by John O’Dowd 2006

One of the most promising recording artists in the mid-1970s was a gorgeous and sexy pop/southern soul singer from Batesville, Arkansas, with the decidedly down home name of Sami Jo. The possessor of a dark, raspy voice full of fire and power, Sami had a top 20 hit in 1974 with the killer ballad Tell Me A Lie and was poised at the very brink of superstardom, when it somehow all fell apart.

A lovely and unpretentious woman of great natural warmth, Sami had all the necessary attributes to make it big in the music business: she was disciplined and hard working; she had a phenomenal voice, and she was beautiful. And with such renowned industry figures as record producers Rick Hall and Jimmy Bowen, artist manager Stan Moress, and publishing mogul Bill Lowery among those who helped guide her career, Sami’s success as a recording artist should have been assured. Yet, somehow, it didn’t happen.

Like so many others who crossed the country/pop landscape, Sami’s story is a textbook example of a singer with tremendous talent who should have made it to the top of the heap, but due to career mismanagement, poor timing, and a series of unfortunate record industry politics, was only able to climb midway up the ladder before landing in undeserved obscurity.

Sami was born Jane Annette Jobe on May 9, 1947, the only daughter of Wes, a construction worker, and Inez, a housewife. The Jobes also had a son, Bill, who was older than their daughter by ten years. Contrary to what has been written in the past, Jane’s nickname of “Sami Jo” was not given to her as a child but would come several years later when she was out on her own and living in Dallas.

“My upbringing was very strict, to say the least. My father was a typical, small town guy, protecting his daughter and making everyone in the county fear him! As a teenager, I had to be in by ten o’clock every night and if I wasn’t, Dad was out on the street, looking for me. When I think about it, though, I’m glad that I had rules and a strict upbringing because I believe it only helped me to be strong and to make the right decisions when I was out on my own.” As a youngster, Sami idolized her big brother. “Bill was the handsome, campus king, given scholarships to the University of Arkansas for football…he was definitely my hero.

“My family belonged to the Nazarene Church and we were pretty serious about it, too. I grew up going to Sunday school every Sunday morning, then on to Sunday service, and back to church on Sunday night and Wednesday night and certainly every night during a revival.”

Sami started singing in church at the tender age of three. “My local radio ‘career’ started when my Aunt Janie decided I should try out for the Saturday morning show that was sponsored by our church. So Aunt Janie took me to the station and I was to sing Jesus Loves Me. Well, I got about halfway through the song and I started to cry…right there, on the radio! My Aunt decided that in order for me to not continue to have stage fright, she had to take me back there the following week, to try again. I sang Zacheus Was A Wee Little Man and I managed to get through the entire song. That was the start of it all. You could say I was a ‘star’ by the time I hit the first grade! (laughs)

“Later, when I was in my teens, I was involved in a lot of beauty contests, mainly because of my sister-in-law, Linda Sue. She was the local beauty queen and she took me under her wing and taught me more than I could ever say. My father was definitely not in favor of this in the beginning, but when I started winning some of the contests, he was more than proud!”

Sami attended Batesville High School where she was a member of the drill team, acted in school plays and sang in the choir. A popular student, she was voted queen of the sophomore class and was later elected homecoming queen in her senior year.

“From my early childhood on, I was always singing in school and in talent shows, etc. When I was a freshman in high school I was asked to sing at the junior/senior banquet. My ‘big’ song was the 1950s pop tune, Three Coins in the Fountain, but pop music was only one of my influences. I always loved r&b, country, rock, gospel and soul music, too, and as a result, all these styles showed up in my music. As a teenager, I especially loved Brenda Lee, Cher and Gladys Knight. Later, when I got into the music business and started recording, some of my fondest and most exciting memories are when I met these fabulous ladies.”

Upon her high school graduation, Sami attended Arkansas College in her hometown of Batesville, where she majored in music. It was during this time that she joined an all-female singing group called The Arkansas College Lassies, which consisted of seven other classmates. “Performing with The Lassies was a wonderful experience,” recalled Sami. “The songs we did in our shows were picked from such wonderful classics as Sound of Music and My Fair Lady. I stayed with the group for nearly two years, when I left college and moved to Dallas. As far as I know, I am the only one who went on to pursue a career in music.

“During my first year with them, we went to The Far East on a USO tour, to sing for the troops. I had never been on a plane before, so needless to say, I was excited, scared and speechless! We flew out to Love Field in Dallas and then on to Japan. My first time away from home was for two whole months. I could hardly believe it.”

Sami moved to Dallas in the mid-1960s, with the intentions of becoming an airline stewardess. “But they told me at nineteen I was too young. By this time, I had gotten a place with some other girls at The Four Seasons Apartments and had begun singing at a nightclub there called The Fifth Season. Back then, both the apartments and the nightclub were considered ‘the place to be’ in Dallas. It was during this time that I got the nickname ‘Sam’ from one of my roommates, which later became ‘Sami Jo’. I wound up using the name professionally.”

One evening Sami was at The Fifth Season with her roommates when one of the girls asked the band to call Sami up to the stage to sing. “The band was new…just starting out,” Sami recalled. “In fact, they didn’t even have a name yet. Anyway, I went up and sang a song with them and the guys really liked my voice, so from then on, every time I was at the club they would invite me up to sing with them. Eventually, they asked me if I would learn some songs and sit in with them on the weekends. After a few weeks, we started building up a following at the club and I was told that a lot of the people were coming in just to see me!”

One of those people was a professional manager named Tony Caterine, who at the time owned most of the major nightclubs in Dallas, as well as a successful management company that handled many of the city’s top entertainers. “It was kind of funny because when Tony approached me,” said Sami, “I told him that I wasn’t interested, and walked off. Now that I look back, I can see that he couldn’t believe it since everyone was trying to get him to represent them and I said ‘I wasn’t interested’! (laughs) I guess that intrigued him because one night he came in and said, ‘I’m buying the club, will you talk to me now?’ Well, eventually I did, and it was the best thing I ever did.”

A confident man, brimming with energy and bravado, Tony Caterine went on to become Sami’s manager—as well as her best friend, the father of her son, and she says, “a lifelong soul mate”. Although they are no longer together as a couple, Sami continues to sing his praises today. “Tony was my first love, my longest love and most probably, the love of my life. We were never married but we are still close and remain the best of friends. Tony is one of those dynamic and charismatic individuals that can master anything he chooses to do. His nightclubs at the time were the most successful in the entire history of Dallas. The Losers Club, in particular, booked some of the greatest entertainers in the business. Anyone who was a star in the music industry appeared there, from The Temptations, Fats Domino, Gladys Knight, Little Richard, Rick Nelson and Brenda Lee, to so many others they would be hard to name. I had the privilege of working with most of those people and it was an unbelievable learning experience for me.”

In addition to her regular gig at The Losers Club, Tony Caterine placed Sami in bigger venues like The Executive Inn’s Carousel Club in Dallas, Lubbock’s South Park Inn, The Amarillo Hilton and the popular Dallas nightspots, Barney Oldfield’s and The Royal Coach Inn. As time went on, Tony got Sami and her band, Candy Mountain, even better gigs in Las Vegas and Lake Tahoe. “I must say something about my band (Kenny Brasher, Steve Slayton, Cass Moore, Richard Theisen and Scott Neilson). They were the best guys. They could sing, be funny, play, and were the most talented group of musicians I could have ever wished for. We were together for many years and I love them all to this day.

“When we played Vegas, Louis Prima became a big fan of mine and would often ask me up on stage with him when he performed at The Sands.

“My first time at Harrah’s in Lake Tahoe was when I met, and worked with, Flip Wilson. I was working in the lounge and evidently Flip wasn’t happy with his opening act in the main room. After the first night, it was pretty much decided by Harrah’s that a change had to be made. Flip and his people came into the lounge to see me sing and afterward they offered me the opening spot in the main room which meant I would be doing his show, as well as mine! It was going to be very hectic but of course I agreed to do it.

“Flip Wilson was absolutely wonderful to me. During his performances, he talked about my show a lot and gave me many compliments, which as a new performer was really terrific for my ego! I will always be grateful to him for that. You know, I’ve heard all the stories that other people have told about their infamous ‘casting couch’ experiences in the business, but I never had that. I found all the stars that I worked with to be supportive and kind…beginning with Flip Wilson.”

By 1970, Tony Caterine had opened another Losers Club, this one in Memphis. Sami was headlining there one night when she met a songwriter and record producer named Sonny Limbo—a man who would prove to be an important catalyst in her career. “Sonny was sitting in the audience with his chair turned backwards and he was totally mesmerized by the show. It was hard not to notice him and his enthusiasm, but I had no idea who he was. After the show, he came up to me, handed me his business card, and told me to call him the next day. He said he wanted to take me into the studio, but to be honest, I really didn’t take him seriously. However, I called him and surprisingly, he did have a studio and we wound up cutting some demos together.”

Sami had hooked up with a man whose outrageous personality and numerous eccentricities were legendary in the Memphis record industry. “To describe Sonny Limbo, God rest his soul, would be very difficult to do,” Sami admitted. “He had a great ear for hearing what others could not. Sonny was a very complicated man with a tremendous amount of talent. Most times, it seems the two go hand in hand.”

Sonny Limbo apparently saw a tremendous amount of talent in Sami, as well. In the 1977 book, Rock and Roll is Here to Pay, by Steve Chapple and Reebee Garofalo, it was said that after he discovered her and took her under his wing, Sonny set out to turn Sami into “your basic city fox”. He instructed her: “Do everything I tell you and I’ll make you a Star.” Limbo told Chapple and Garofalo, “She did. I did. And we did. That kind of attitude, an outasight voice and a motherfucker song—to break a chick that’s what it takes. Then, if she looks good and has big tits, she just might make it.”

Obviously, Limbo was a total character, but today Sami will only say: “Because of some serious personal problems and insecurities, Sonny was his own worst enemy. He had a sadness that could never be explained and I truly believe that it led to his early death.” After shepherding such acts as Bertie Higgins (Key Largo) and country supergroup Alabama into stardom, Sonny Limbo died some years ago.

In late 1970, Limbo managed to get Sami a singles deal with Rick Hall’s Fame Records in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. Home to the legendary ‘Muscle Shoals Sound’ of soul, country and southern rock, the Fame enterprise had, since its inception in the early 60s, played host to such stellar r&b acts as Aretha Franklin, Wilson Pickett, Clarence Carter and Candi Staton, and by 1970 it was branching out to record more pop-flavored performers like Mac Davis and The Osmonds. Rick Hall had great faith in Sami’s talent and took her into the studio with his sidemen Barry Beckett, Roger Hawkins, Jimmy Johnson and David Hood, where they cut a mainstream pop song, Don’t Hang No Halos On Me (Fame 1481), released February 1971. The tune was written by Wayne Carson Thompson, who had penned The Box Tops’ # 1 hit, The Letter, in 1967.

“Don’t Hang No Halos…was a pretty good record but nothing much happened with it,” Sami recalled. When the song failed to make the charts, she resumed her club work but returned to the Fame studios the following year to cut another single. This time, Sonny Limbo produced her session and they released Big Silver Angel (Fame 91003), which was the kind of uptempo, horn-driven pop record that was so popular during that period. But just like her previous record, the single failed to chart, ushering in Sami Jo’s exit from Fame Records in late 1972. Still, “It was a good place for me to start,” Sami said, “and I got to work with some dynamite people there.”

Despite her obvious disappointment, Sami forged on—as did Sonny Limbo, who was, after all, determined to make her a Star—and in 1973 he got Sami a new record deal with MGM South, an offshoot of MGM Records. It would prove to be both a good, and a bad, move for Sami’s career. According to the Internet article “MGM South Album Discography” by Mike Callahan and Peter Preuss:

“MGM South was a short-lived subsidiary label of MGM, primarily directed toward country music. There were about 34 singles issued on MGM South, and two albums. The artist roster included Tommy Roe, Dennis Yost & the Classics IV, Billy Joe Royal, Sami Jo, Christopher Paul, Us, Shawn, Glen Wood, and a few others. The first two singles on the label, released in the fall of 1972, both charted. Tommy Roe’s “Mean Little Woman, Rosalie” [MGM South 7001] made #92, while Dennis Yost and the Classic IV’s “What Am I Crying For” cracked the top 40. Each artist had a followup single on the charts also…Roe with “Working Class Hero” [MGM South 7013, #97 pop and #73 country in May, 1973], and Yost with “Rosanna” [MGM South 7012, #95 in March, 1973]. A planned Tommy Roe album was canceled, and the Dennis Yost album was issued, but didn’t chart. Singles by Billy Joe Royal didn’t chart at all. Part of the problem of MGM South was identity. Rock and Roll/Pop retreads like Tommy Roe, Billy Joe Royal, or the Classics IV were not received as country acts, no matter how hard MGM pushed them. Royal would later find a home in the country charts, but that was over a decade in the future.”

In its brief time in existence, Sami Jo would prove to be MGM South’s most successful act. “Sonny Limbo had gotten together with Bill Lowery, who was head of the label, and he brought me to Atlanta to meet with him. What is really funny is that Bill was known to not be very fond of female singers, but he liked me so he said he was willing to give me a chance. At the time, the guys in charge of signing new artists at MGM were Stan Moress and the Scotti Brothers (who went on to manage teen star Leif Garrett in the late 70s). Stan later came out to Dallas, watched my stage show then offered me a deal and said, ‘Baby, I’m gonna make you a Star!’ (laughs) You know, the same line that Sonny had used. Stan and I have laughed about this many times since because he says that I looked at him and said, ‘Sure you are.’ Well, he did wind up helping me a lot. Stan Moress and I became great friends and we still are to this day.”

In 1973, Sonny Limbo found a dramatic, country/pop ballad with southern soul overtones, called Tell Me A Lie, for Sami to record, and it would become her biggest chart hit. A secretary at Bill Lowery’s studio who had heard some tracks Sami had cut with Sonny reportedly wrote the song with Sami in mind. Later covered by such disparate acts as soul singer Bettye Lavette, German artist Tina Rainford and country star Janie Fricke, the song told the story of a lonely woman who meets a man in a bar and reveals to him the kinds of lies some men tell their one-night stands. By the song’s end, after he’s spent the night with her, she is begging him to tell her what she wants to hear: namely, that he’ll “be back one day”.

Tell Me A Lie was a bona fide hit for Sami, reaching # 14 on Billboard’s Easy Listening Chart and # 21 on the Top 100 Pop Chart. Sami made a flurry of TV appearances in support of the record (American Bandstand, among them) and then went back into the studio to record her first LP for the label. The resulting album, titled It Could Have Been Me, showcased Sami’s strong, husky voice and ably straddled the fence between country, MOR and pop. With the album’s tracks arranged by The Georgia Power Rhythm Section (with future Dolly Parton producer Steve Buckingham on lead guitar and co-producer of the album, Mickey Buckins, on percussion) and with the additional support of The Memphis Horns, the record had a soulful, contemporary sound strongly akin to the music such acts as Joe South and Tony Joe White were also making at the time. In fact, along with Sami’s follow-up single It Could Have Been Me, which reached # 31 on Billboard’s Easy Listening Chart, the album boasted covers of South’s Games People Play and Harry Nilsson’s Without You, and even included a controversial song about the sordid life of an Atlanta call girl, Lovely Daughter.

“During this time people began disagreeing about what kind of singer I was,” said Sami. “Some said blues, some said country, others said pop, while others called me a ‘white soul singer’. Needless to say, it was a very exciting time (because of the success of Tell Me A Lie) but also a very confusing time—not only for me, but for the people around me, too. The main concern was ‘which way should we go with her’? We also had to hold up the release of the album because MGM South’s president Gil Beltron decided he wanted me to record his favorite song (Without You), so we had to go back into the studio and add it to the album. Why, I don’t know, but he insisted.

“Also, Sonny Limbo was having some serious personal problems around this time and I was working more with Mickey Buckins and a lot of other people, which made things quite confusing. Finally, Steve Buckingham, who later became a top executive at Sony Records, took over my sessions and helped me finish the album. Steve also was to become a wonderful friend.”

One of the highlights of Sami’s career was the night she performed with The Atlanta Symphony with Steve Buckingham conducting the orchestra. “The city of Atlanta had declared it ‘Bill Lowery Day’ as a tribute to Bill’s many accomplishment’s in the industry. Along with several of the other artists that Bill had helped, I was asked to perform that night. I sang Tell Me A Lie and the audience responded so warmly. It was a very exciting experience…one of the most exciting experiences of my career, I think.”

Sami’s album It Could Have Been Me went to # 32 on Billboard’s Top 100 Pop Albums Chart—not a bad showing for an artist’s debut effort. Having already appeared on TV’s American Bandstand, she went on to perform on The Bobby Goldsboro Show, Hee Haw, Pop! Goes The Country and The Jimmy Dean Show, among others. The August 15, 1974 issue of Rolling Stone magazine featured an article on Sami and her photo also graced the cover of both Cashbox and Record World, two important trade papers of the day. “It was definitely a whirlwind,” Sami said, “as I was also performing in many of the country’s top show rooms at the time. My career had taken on a life of its own but I loved every minute of it.”

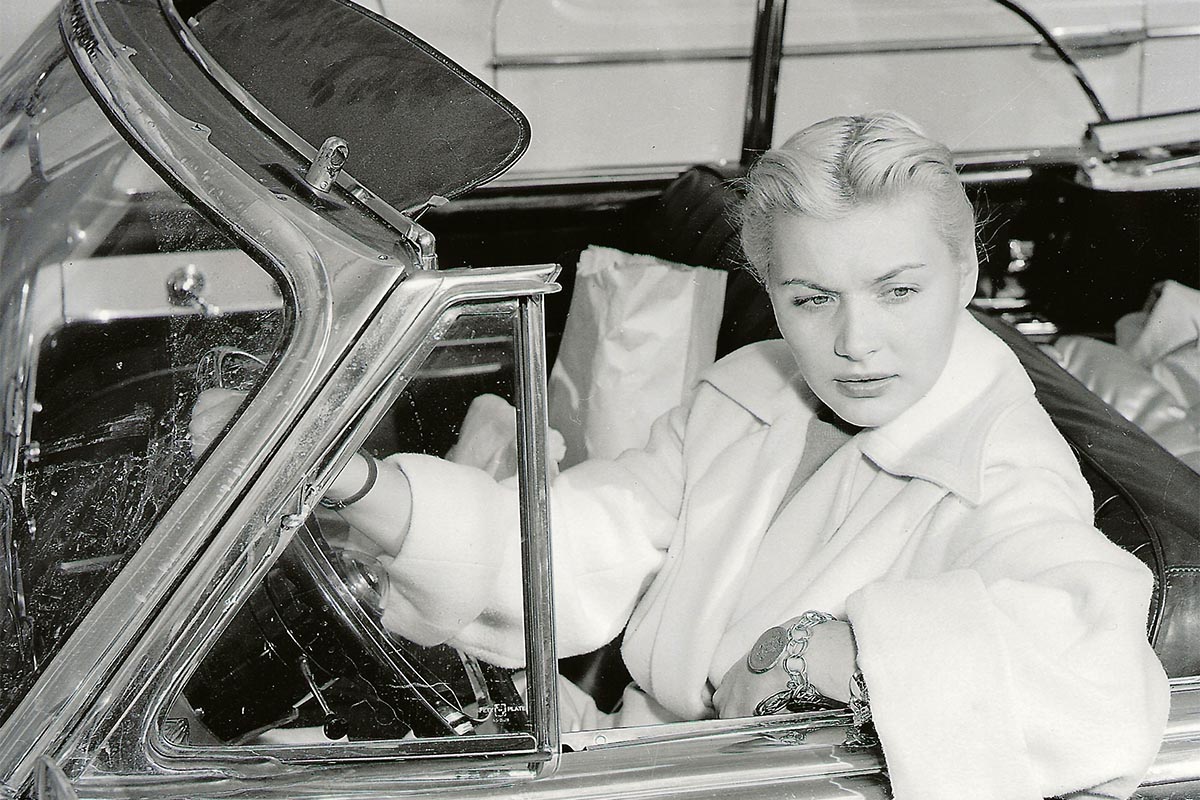

During this time, a news article reported that Sami was living in “a sexy, new townhouse on Dallas’s Northwest Highway”, and that she had acquired “three Mercedes sports cars and a Mark IV Continental.” Sami admitted, “I was living very well but I was also careful about making some good investments…for my future. That was due to Tony Caterine’s influence.”

On the heels of her success with Tell Me A Lie, Sami appeared with such 70s icons as Mac Davis, Ray Stevens, Tony Orlando and Dawn and Jim Stafford on stages in Las Vegas and across the country. She said, “I felt so lucky being able to appear with all these great stars. I can honestly say that every one of them was kind to me, and they were all so supportive. I don’t remember anyone being hard to deal with or anyone making me feel like I didn’t belong.

“Most entertainers have horror stories of the ‘stars’ they dealt with, but I really don’t. Everyone was very generous to me, and to everyone around me. I am very grateful for that.”

In January 1975, a third single entitled I’ll Believe Anything You Say was released off Sami’s album, but it only reached # 62 on Billboard’s Hot Country Singles Chart. Shortly afterwards, the MGM-South arm of MGM Records folded and was absorbed by the larger parent company. Sami’s recording contract was one of the few from the subsidiary label that was saved. “All of a sudden I was told that I was going to L.A. to record with MGM Records president Jimmy Bowen,” she said. “So, I went!

“The MGM South period of my life was wonderful and at the same time, very frustrating and confusing,” Sami admitted. “I loved the people and trusted them, and I wanted so badly to be successful for them. It just seemed that we couldn’t quite get things off the ground after Tell Me A Lie. I went to MGM Records in L.A. with the belief that things were going to be different.”

Sami recorded her eponymous second album, a lushly orchestrated, full-out pop collection, at Hollywood Sound Recorders. “I had always heard of Jimmy Bowen and knew of his wonderful work with Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin, so needless to say, I was very excited to work with him on my next album. The material he chose for me to record came from people like Billy Joel (You’re My Home), Kim Carnes and Duke Ellinson (Changin’) and Jim Weatherly (Storms of Troubled Times), and they were all phenomenal pop songs. Jimmy had the best players in L.A. working on my record and I had no reason to think it wasn’t going to work. I obviously wasn’t very knowledgeable about the business in those days.”

Half the songs on Sami’s album were written by Weatherly (who had penned Gladys Knight’s mega-hit Midnight Train to Georgia) and I asked Sami if it was a conscious decision of Bowen’s to record her in a similar vein to Knight, who was one of her childhood idols. “Not to my knowledge,” she answered, “but Gladys’s music had always made a strong impact on me so I guess Jimmy may have heard that, too.

“The album we did in L.A. was an experience I will never forget. Jim Weatherly, as well as Kim Carnes (whom Jimmy Bowen was also producing), were at most of my sessions. I remember that Kim was pregnant at the time. I absolutely loved both of them as writers and felt very honored that they wanted me to do their material. My experience during the entire session in L.A. was something I will always cherish.”

The two singles off Sami Jo were the oft-recorded Carnes ballad You’re A Part Of Me and Alan O’Day’s Every Man Wants Another Man’s Woman and though both were highly commercial cuts, neither record charted. It would be back to the drawing board for Sami, to try to find another hit.

In the spring of 1975, with MGM slated to become Polydor Records the following year, Jimmy Bowen suddenly left the label and moved to Nashville, leaving Sami without one of her biggest advocates. As a result, her recording career stalled until 1976, when she was moved over to the newly-formed Polydor, to record two singles, God Loves Us (When We All Sing Together), which was released in May of that year and went to # 91 on Billboard’s Hot Country Singles Chart, and the languid Take Me To Heaven. By this time, Sami’s various handlers and the new powers-that-be at Polydor Records thought that it might be best to redirect her as a country artist rather than as a singer of glossy pop material. Sami was also back working with Sonny Limbo and Mickey Buckins on these sessions.

“Being back in the studio with Sonny and Mickey was something I had looked forward to and I loved every minute of it. Unfortunately. Polydor didn’t do very much to promote those two songs, which I honestly don’t understand. God Loves Us…was a great song and a good cut, but the label didn’t seem to have any interest in me once Jimmy Bowen left. It was like they just dumped the singles out there without much thought, which is really not fair at all.”

After Take Me To Heaven was released in September 1976 and only went as high as # 67 on Billboard’s Hot Country Singles Chart, Sami’s recording career hit another dry spell. Still, she continued to be a big draw at many major hotels in Vegas and Lake Tahoe throughout the late 70s. She performed in the main rooms at The Playboy Club, Harrah’s, The Hyatt Regency, The Flamingo, The MGM Grand and The Sands, and opened shows for everyone from Bob Hope to Kenny Rogers.

“I wish I could say I had some exciting or naughty stories about these guys, but honestly, they were all wonderful to me. They treated me with the utmost respect and tried to help me any way they could.”

During this period, Sami was still hoping to get her recording career going again and in doing so, try to recapture the magic that Tell Me A Lie’s success had brought her. In April 1979 it was reported in Billboard magazine that she would be recording her third album that July, with the proposed first single being a blues song called Trouble Is…Amazingly, though Sami hadn’t had any new product in the marketplace for three years, she had somehow held on to her deal with Polydor, though she was now part of its Mercury Records roster. But sadly, this association, like all the others before it, wouldn’t last. Both the single and the album Sami recorded for Mercury were later shelved.

“I recorded some wonderful songs for the label, but they never got a chance. It’s a very unfortunate thing but it happened to me, and to a lot of other people in the business, too. I’m not sure if the average person out there knows just how often it does happen.”

After a two-year break from recording, if not performing, in 1981 Sami came back as ‘Sami Jo Cole’ and was signed to Warner Brothers-owned Elektra/Asylum Records in Nashville. “By then it was decided that maybe it would be better, professionally, if I used a last name, so I took my son Tony’s middle name, Cole, which everyone seemed to like.” Sami’s former producer and loyal mentor Jimmy Bowen was now the vice-president and general manager of Elektra and he was eager to work with her again. “It was another singles deal,” she said. “After cutting two albums, it was like starting over from scratch, but Jimmy Bowen said he had a lot of faith in me and believed we could find a hit together.”

At the time, the combined rosters of Nashville’s Elektra and WB Records country divisions totaled a whopping 54 acts—with everyone from Hank Williams, Jr. and Nancy Sinatra to Conway Twitty and K.T. Oslin vying for radio time. Despite the label’s being ridiculously overloaded with artists and the very real possibility that she would once again be lost in the shuffle, Sami said that Bowen made her feel he was intent on grooming her for big things there. “Jimmy was always patient and kind and very positive as to what he thought we could accomplish.”

The first 45 out of the chute for Sami at Elektra Records was a striking, MOR-flavored ballad entitled One Love Over Easy, co-produced by Bowen and his wife at the time, Dixie Gamble Bowen. It was an extremely powerful piece of material, both lyrically and musically, and was probably one of Sami’s most brilliant recorded performances. Yet, despite its excellence, and its getting rave reviews by journalists like Kip Kirby at Billboard magazine, the record only went to #76 on the charts. Sami attributes its lack of success at the time to a puzzling lack of promotion at her label. “There was just too much product (at Elektra) and only a certain number of available slots. Without any real promotion, a record doesn’t stand much of a chance.”

Despite the single’s failure to become the chart hit it should have been, Sami continued her hectic touring schedule. In those days, her agent was Marty Beck at The William Morris Agency and she was pulling in over 200 show dates per year. During this time, she also began touring a lot with labelmate Eddie Rabbitt, whose longtime manager Stan Moress had signed Sami to MGM South and had remained a steadfast supporter of her career. Eddie, too, would later claim that Sami was among his favorite singers.

“My memories of Eddie Rabbitt are nothing short of fabulous,” Sami revealed. “He was supportive and wonderful to me and I could never explain how much he meant to me. He was such a gentleman and so talented and I feel fortunate to have shared many good times and conversations with him. I was so sorry when I heard of his illness and his untimely death. It broke my heart.”

Sami’s camaraderie with Eddie was evident when she chose to redo one of his earlier hits, I Can’t Help Myself (Here Comes The Feeling), as her next single for Elektra. Although Sami gave the song a fresh and unique interpretation and Jimmy and Dixie Gamble Bowen were again at the helm, the record fared even less successfully than its predecessor, and only went to # 82 on the charts. Still, there was a certain hoopla surrounding the song—not in the States, however, but in Korea, of all places! “I had the privilege of performing Eddie’s song at The World Music Festival in Seoul. I was asked to represent the United States in the competition, and amazingly, I won first place with that song. I was on cloud nine…even though my winning was never even announced here in the States!”

Upon returning home, Sami was invited to fly out to Los Angeles to audition for a co-host position of a new national TV show called Country’s Top 20. She got the gig and in late 1981, taped several episodes of the show in Las Vegas. “That was such a thrill for me. I co-hosted it with Dennis Weaver and he was a sweet, lovely man. We had a ball together. Everyone with a top 20 country hit at the time was on the show and I thought it was very well done.”

Sami sang on the show, as well—not her own records, but other artists material. While there was still the belief at Elektra that Sami’s recording career continued to have great potential, she was starting to wonder if real stardom was ever going to happen for her.

By March 1983 Sami had been moved over to the WB side of WB/Elektra-Asylum Records and was scheduled to record an album with Jimmy Bowen, but industry politics once again reared their ugly head and prevented the project from ever coming to fruition.

“I really don’t know what to say about what happened to that album,” Sami said, “but I guess I was getting used to it by now. I always seemed to be in the midst of labels changing presidents or other problems I had absolutely no control over. It definitely wasn’t good for my career. I only wish I had the opportunity to do it all over again. Knowing what I know now, I can assure you it would turn out differently! Back then, I let other people decide what I should wear, how I should look, and what songs we should release…or in this case, not release. (laughs) That was my mistake, but only because I was too trusting and uninformed to know what was good for me.”

Late in 1983, Sami took a break from her dormant recording career in Nashville and moved to Oklahoma, where she, Tony Caterine and their six-year-old son Tony Cole (born May 21, 1977) settled into a three-story, white brick mansion in a plush South Tulsa suburb. A news clipping from that period described Sami’s new home as “beautifully appointed, with five bedrooms and massive hallways filled with expensive, pre-Columbian sculptures.” Sami smiled at that description and said, “Yes, I found a real southern mansion and I fell in love with it, too. I had decided by then to stop traveling so much since Tony Cole was getting to be school age and Tulsa was a nice place to live. I continued to do some shows, as well as ad jingles and radio commercials, but I mainly wanted to stay home for Tony.”

Despite her aborted album project from earlier that year, Sami was still under contract to WB— and still hoping for a break. Things, however, were about to get a lot tougher, as Jimmy Bowen explained in his 1997 memoir, Rough Mix (co-authored by Jim Jerome):

“The new WB (post 1983) had two full staffs and 54 acts—which meant more firings, more enemies…I wound up having to drop more than half the 54 artists on the combined roster…When I merged Elektra and WB, I got rid of most of the Warners people and kept my own staff from Elektra…I brought in Jim Ed Norman, who I’d known years earlier when he played in (the band) Shiloh, to be my head of A&R.”

Although Sami had survived the first round of cuts at the label, the prevailing opinion there was that she desperately needed a hit record to continue to justify Jimmy Bowen’s longstanding support of her career. It was decided to bring in a new producer for her, and who better than the new head of A&R himself, Jim Ed Norman?

An extremely talented man whose deft production work helped make Anne Murray’s early-1980s comeback a huge success, Norman and Sami collaborated on what would arguably be her shining moment on record: an exquisite remake of Brenda Lee’s 1961 pop hit, Emotions. Beautifully produced with a lush arrangement and a cool, retro sax solo at the end, the song was highly commercial, and Sami’s vocal work on it was nothing short of sublime. But, although singer Juice Newton had won a Grammy Award a few years earlier with a similar treatment of Brenda Lee’s Break It to Me Gently, and Crystal Gayle would have a # 1 country hit in 1986 with her Jim Ed Norman-produced remake of Johnny Ray’s Cry, Sami’s record, while highly reminiscent of both those songs, disappeared almost immediately upon its release. For reasons still unknown to her, Emotions was shipped to radio in March 1984, but was then promptly pulled by WB. As a result, the single never made it into most record stores and today it remains a highly obscure (and thus, much sought after) commodity on the collector’s market. Of all the puzzling and unexplainable injustices in Sami’s career, this was the one, she says, that hurt the worst.

“To this day, I believe that Emotions and its flip side, I Can’t Help The Way (I Don’t Feel), were two of the best songs I’ve ever done. But the truth of the matter is, WB did not get involved to promote the record. Why, I don’t know. It was a total waste of time and money. I will always feel that those beautiful songs and the efforts of Jim Ed Norman and I were totally neglected and that the record company did us both a complete disservice.” A sad and bitter Sami left WB after all her hopes for the success of Emotions went up in smoke.

Following the end of her three-year deal with Elektra/WB, Sami resurfaced in 1985 on Southern Tracks Records, a tiny, independent label owned by one of her earliest mentors, Bill Lowery. Sami seemed to go full-circle when she also reunited with Sonny Limbo, who produced her first single for the label, a somber, slow-moving ballad entitled I’m Going Away (Before You Can Say Not To Go). Considering all that she had been through, perhaps it was no surprise to Sami when the record failed to chart. Though she would later record a duet with fellow 1970s pop singer Sammy Johns (of Chevy Van fame) in 1986, the song, Fallin’ For You, received limited airplay, sending a clear message to Sami that her recording career was definitely winding down.

“In the late 80s I did go back into the studio to cut some sides with producer Snuff Garrett. I was excited because I loved all the music he’d done in the 70s with Cher (Half Breed, Dark Lady, et al) and he wanted to record me in that same vein. Snuff was wonderful to me. Once again, we did the session, got along great, and then nothing happened with our efforts. There’s a lot of fantastic stuff I cut over the years that just stayed in the can, as they say. I have no idea where any of it is now, or if it even still exists.”

When her singing career first began to slow down, Sami got a job outside the business, managing TC Sportswear and Accessories in Tulsa. “TC” was Tony Caterine, Sami’s ex-romantic partner and manager. “By that time, I was totally disillusioned about the music industry and I just wanted out of it. I can’t say the feeling of running a shop was the same as performing, but I was so burned out, I needed to do something different in my life.”

After four years, Sami left TC Sportswear for a management position at Burgundy’s Fine Gifts, also in Tulsa. “My best friend Dee Sallee owned it and I loved working there. We sold beautiful collectibles like Lladro, Swaroski Crystal and Hummels. I learned a lot and stayed there for about five years, when Dee closed the store.”

As if her disappointment over her former recording career wasn’t upsetting enough, Sami’s personal life took a major hit in 1993 when she was diagnosed with cancer. “It was initially breast cancer,” she revealed, “but then it got into my system to the point that my only option was to have a bone marrow transplant. Thankfully, because of two wonderful oncologists, Dr. Charles Strand and Dr. Allen Keller, I’m alive today. I was in St. Francis Hospital for 30 days, then went home to a sterilized house and wasn’t allowed to go to any public places for another 60 days. Basically, I was dealing with the cancer for all of 1993 and 1994.” Thirteen years later, a grateful Sami reported that she remained cancer-free.

“Going through something like that makes you stop and think about many things in your life. I was told that because of the extreme doses of chemo I received that I might never be able to sing again. Thank God, that proved not to be the case. It’s funny, but during that whole ordeal the main thing I thought about was whether I would ever be physically able to perform again.”

In November 2005, Sami’s son Tony and his fiance, Andrea, had a baby boy, Maximus Anthony Caterine, giving Sami her first grandchild. “Max Anthony is a beautiful baby…and the light of my life,” Sami said proudly. “He is by far the best thing that’s ever happened to me.” The early part of 2006 brought some challenging transitions in her private life, but Sami came through them later that year with a renewed interest in relaunching her singing career. “For an entertainer, there is nothing like the love and applause of a live audience. Nothing could ever take the place of the feeling I have when I’m singing and going for ‘the note’! I would love to have the opportunity to perform—and record—again. The problem is that no one seems to want to have an older woman or older person making music. A friend told me the other day that he heard a talk show host—I think it was Neil Bortz—talking about hearing a female singer who was 65 years old and how wonderful she was, and how she couldn’t get any work because of her age. Isn’t that a shame? But I guess that’s just the way it is.”

Sami has a rather novel idea on how that problem might be solved. “I think that Simon Cowell (American Idol) or someone of his stature needs to put together a weekly TV show about what happened to singers from the past (say, from the 1960s to the 1990s). They could call it What Happened To…? and have the performers sing their one or two monster hits on the show. Hey, I would even be happy to be one of the hosts and help cheer on some of the wonderful talent that is still out there that no one gets to hear anymore! How much incredible talent is out there that had the one or two hits, and were never heard from again? I assure you, it often has nothing to do with talent—it could be due to bad timing, record label snafus…a lot of things. I know that it happened to me so why could it not have happened to a lot of other people, too?

“I guess if I were to be totally honest, I would have to say that nothing in this world could ever make me feel the way that performing does. Singing was my joy and my therapy. I loved what I did, and yes…I miss it. I miss it a lot. I think back on those days in the late 70s and early 80s when I was working the best show rooms in the country, with people like Kenny Rogers and Bob Hope. It was wonderful. These days, I just sing in my car…

“Sometimes when I watch music shows, whether live or on TV, there is a sadness that takes over me and makes me feel like I am missing out on so much. I guess the question is: is there anyone out there who cares enough to bring a lot of us back? Is there anyone out there who is willing to take a chance and say, ‘We miss hearing these people…let’s give them another shot?’

“I can hope…can’t I?”